For the first time, on November 20, 2024, the Dia da Consciência Negra (Black Consciousness Day) was recognized as a national holiday in Brazil. The date marks the death of Zumbi dos Palmares, the leader of the largest Brazilian quilombo, who was beheaded in 1695 by the Portuguese Crown—his head displayed as a trophy in a public square (to dispel, it is said, the myth of his immortality). The quilombo was a community of enslaved people who escaped from white-owned plantations, where they were kept imprisoned in the senzalas, the quarters designated for them—hence the name of a classic (and controversial) Brazilian text, Casa-Grande & Senzala (1933), by sociologist Gilberto Freyre.

The day aims to celebrate the fight for racial equality, to commemorate the resistance of Afro-descendant peoples, to promote concrete actions of reparation, as well as to increase Black representation in Brazilian society. The documentary Black Rio! Black Power!, directed by Emilio Domingos, achieves this goal by telling the story of a cultural movement that remains underappreciated. The culmination of 10 years of research, the film has screened at 24 international festivals and won several awards. When talking about Rio de Janeiro, the most obvious associations are samba, bossa nova, and, more recently, funk—little is said about soul. However, not recognizing the thread of continuity between them—and also with hip hop—would be like calling funk “a child of an unknown father.” And Furacão 2000, the record label and producer of the dance parties from that era, represents exactly this line of continuity.

According to journalist Silvio Essinger (O Batidão do Funk, 2005):

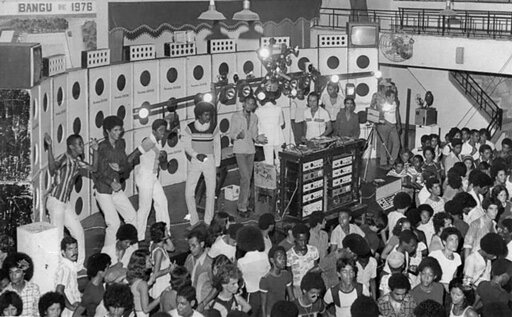

the choice of 1976 as the milestone of the movement is because it was the year it became visible beyond its own attendees, thanks to the report Black Rio: the (imported) pride of being Black in Brazil, by Black journalist Lena Frias, a specialist in Brazilian popular music, and photographer Almir Veiga, published in Jornal do Brasil.

In reality, these were years in which “the phenomenon of Black dance parties on the outskirts of Rio” began to draw the attention of the authorities. Brazil was under a dictatorship, and the military viewed with suspicion a movement that brought together more than 15,000 young Black people from the suburbs, who not only danced but also organized politically.